What’s going on with Ofsted’s inspection of special schools?

28/2/2020

Do you know the overall proportion of good and outstanding schools in England?

Whilst we are all familiar with the flawed governments statistic: “1.9 million more children are in good and outstanding schools” (which does not account for growth in pupil numbers), the true answer is far more interesting.

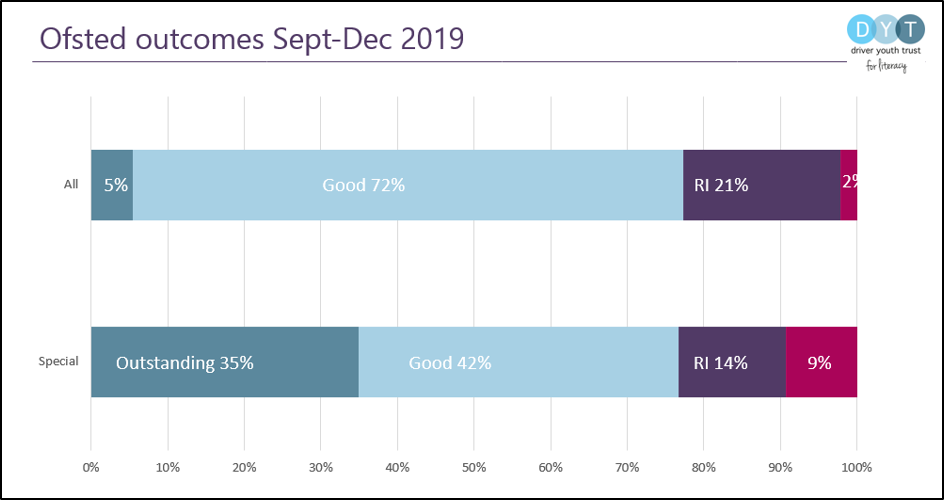

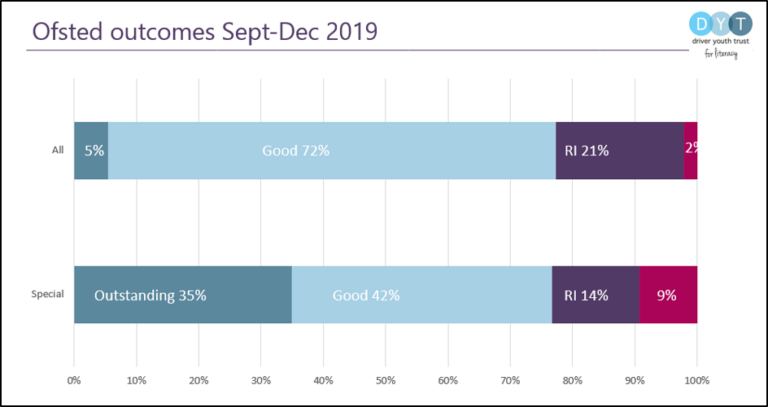

According to Ofsted’s National Director of Education, 86 per cent of schools have been judged good or outstanding at their most recent inspection. If you look at the new Education Inspection Framework (EIF) that was introduced last September, those getting the good and outstanding judgements for overall effectiveness has dipped to 77 per cent (based on just 840 full inspections and section 8 inspections of previously good and outstanding non-exempt schools). But if you run this analysis for the 50 special schools that were inspected in the first three months of the new EIF, the picture is rather different.

Not the headline. Spookily – given the size of the samples – exactly 77 per cent of special schools are good or outstanding (full inspections and section 8 inspections of previously good and outstanding non-exempt schools), the same as the proportion of mainstream schools. But drill down and the picture is very different. The judgements that in mainstream schools that are the outliers – Inadequate and Outstanding – are far more common in special schools. Of the 77 per cent of special schools that are Good or Outstanding, nearly half of them (35 per cent) are Outstanding. This compares to just five per cent of all schools awarded this accolade. Meanwhile at the other end of the scale, nearly one in ten special schools are judged inadequate. This compares to just two per cent of all schools.

To put it another way, a special school is 600 per cent more likely to be judged outstanding than a mainstream school; 350 per cent more likely to be judged inadequate.

So, is this the EIF, or is this special schools?

As with everything in education, it’s probably a bit of both. To start with, the phenomena is not that new. Probably because of the absence of validated data, there have always been more outstanding special schools. However, if you removed the special schools from the sample of all schools inspected under the new EIF, the proportion of inadequate schools would halve.

The source of the problem may lie in the fact that the evidence base used to support the development of the EIF failed to look specifically at special schools or special educational needs. In addition, the new focus on quality of education and curriculum, whilst broadly welcomed by most, may be particularly challenging in a special content where there are often more cross-subject and/or cross-age classes. In a special school setting, doing a ‘deep dive’ in one subject could be taking a swim in some rather muddy water. The experience your inspector has of swimming in these conditions could therefore make a considerable difference to the outcome.

Special schools are by their very nature, special. It is therefore harder to compare them and to hold them to account against a single framework. But if the number that are ‘Good’ are now in a minority, it is perhaps time to look at the quality of education they are providing and rethinking how we are judging them.