Broad, creative and inclusive: the case for a renewed focus on literacy

2/12/2021

Last week, I was fortunate enough to co-host a workshop at the Fair Education Alliance Summit to talk about some of the barriers young people face to literacy. Alongside co-hosts from First Story and CLPE, we discussed the importance of broad and inclusive literacy for the development of every child.

Our presentation followed the publication of an open letter calling on the government for greater investment in literacy. We’ve engaged with the DfE and the new ministerial team in the hope that they will lead a better vision for literacy through the forthcoming white paper.

If we’re serious about addressing literacy in its totality, we need to think beyond the narrow approaches currently seen in schools, advocated by policy.

Literacy is fundamental to whole child development

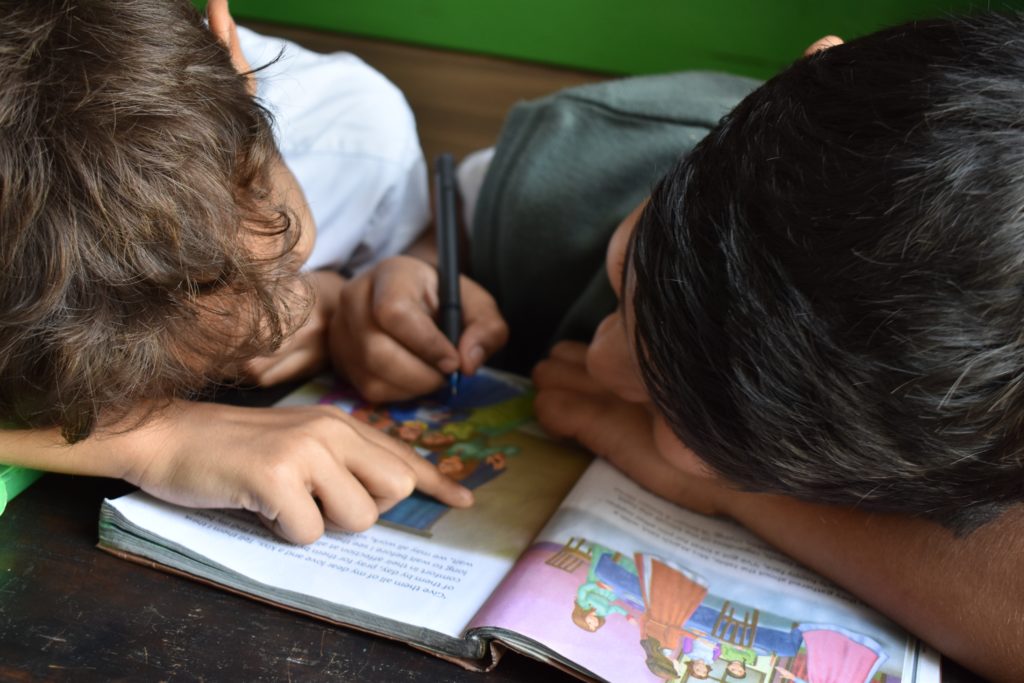

Enabling young people to express themselves and exercise agency in their personal lives could not be more important to their development and education. Within literacy this means ensuring they have the skills to understand and comprehend what they see, hear and read so that they can make decisions that are right for them. Speaking, listening, comprehension and inference strategies are fundamental to developing a literacy child. These need to be a priority at every stage of education.

But this is not enough. These skills need to be situated within the cultural sphere children and young people find themselves in. Teaching them how to engage with the key ideas and thinkers of our time will help raise cultural capital and overcome literacy difficulties beyond the purely functional.

There are gaps in provision, practice as much as outcomes

A narrowed approach to literacy, at the cost of language development beyond early years, is a perennial mistake. Developing language, vocabulary and oracy skills will promote child development and broaden learners’ abilities to engage with the whole curriculum.

We need a vision and guidance on building a coherent curriculum for literacy (and numeracy) which accepts the individual starting points of young people. Being more creative with book choice and using visuals to aid reading, such as CLPE’s Power of Pictures, are simple, effective and low-cost alternatives to pricey schemes.

Persistently low literacy rates for those who struggle most with reading, writing and communication – who may have SEND or other characteristics – is demonstrable evidence that the current approach just isn’t working.

The solutions are simple but need to be delivered strategically

These is no point in making assumptions about achievement of expected standards in reading and writing if we do not have the tools to ensure young people can reach them. Likewise, where schools have the greatest literacy challenges, they should be supported with targeted high quality professional development to boost high quality teaching.

Collaborating with trusted third parties, such as DYT, First Story or CLPE, is a sure way for schools to benefit from the innovative and values-led programmes offered by our sector. These is also a case to look beyond specialist providers and consider the role of the creative sector to engage and inspire young people through expression and understanding.

Schools should be helped to acquire additional resources, including books and other reading materials, provide cultural experiences and embed literacy within and across everything they do.

Only through a truly holistic and systematic approach can we hope to improve literacy and support whole-child development. This reflects the thinking behind DYT’s CPD offer, which combines the best available evidence to deliver low-cost yet highly effective support.

Chris Rossiter, Chief Executive

Chris originally trained as an applied psychologist and has worked across the private, public and charitable sector for over fifteen years. He has particular expertise in special educational needs and disability, and organisational psychology. He is a primary Chair of Governors, Trustee of the Astrea Academy Trust, member of the literacy sub-committee of the Hastings Opportunity Area and Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts. Married to Geoff, Chris lives in Berkshire and has interests which include cycling, wine and twentieth century art. Chris’ real passion is his Labrador, Dolly.